How to love fashion and Mother Earth

Understanding the impact of our clothes on the environment and society

Getting this in just under the wire for April’s Earth Month, but I’ll say I’m being fashionably late!

Fashion sustainability seems to be the topic on everyone’s lips these days—right behind speculation about how impending tariffs will impact the industry. Is [insert brand here] sustainable? What are their labor practices? How is their pricing structured? What’s their environmental impact? First, let’s applaud that people are even starting to ask these questions and think critically about where their clothes come from.

Not to be one of those obnoxious people who say I liked a band before their hit song, but… I first started thinking about fashion sustainability in 2017 after I fully ugly cried on the elliptical at my college gym watching The True Cost. (As an aside, this documentary inspired an idea for my team’s pitch for a business competition in college and the video of it is still somewhere on Facebook)

The True Cost examines the environmental and societal impact of the fashion industry. It was also the first time I was aware of the negative implications of an industry I had grown up worshipping. I was embarrassed by how I previously thought about clothes, thinking “the more the merrier” and mindlessly scrolling Zara for items I didn’t need. It was pretty easy after that to sever my relationship to “fast fashion”, but I still thought of shopping at J.Crew, Madewell, Everlane, and anything considered “contemporary” or mall brands as fine. They weren’t the worst offender, so I didn’t think they could be that bad.

Unlike my break-up with fast fashion, there wasn’t one defining moment that pushed me to re-evaluate my relationship with those brands. Instead, it was a slow awakening. I started to notice how my inbox was constantly flooded with sales, and I couldn’t imagine paying full price for J.Crew when I knew it would be marked down in a few weeks. I began to realize that this business model couldn’t be sustainable for the company or, more importantly, for the planet. If brands were producing so much that they were constantly running a sale, something was off. As consumers, we’re taught to constantly consume, and that consumption is positive. We’re told that if we don’t buy this [insert this season’s it item], we’re uncool. I found that when I was shopping, I was often buying for the idea of the woman who would own this dress rather than the dress itself. I thought owning a particular piece would make me the woman I wanted to be. Needless to say, that’s a hamster wheel—you’ll always need another dress, pair of jeans, or handbag to “complete” you. (This is probably a sneak preview of another essay…)

Since it’s been 10 years since The True Cost came out, I wanted to find some more recent reporting on the state of the fashion industry. I read this report from Remake, an independent advocacy organization focusing on fair pay and climate impact. Every year, they publish a report on the current state of the industry and examine brands on 6 factors: (supply chain) traceability, commercial practices, environmental justice, wages and well-being, raw materials, and governance. I read the 55-page report, so you don’t have to; this quote sums it up nicely.

“Fashion consumers, too, are forced to compartmentalize when they shop. They search for justifications for their natural desire to look and feel beautiful, while participating in a system they know involves exploitation of garment workers and toxic pollution.”

YES! No matter how good a new top or dress makes me feel, it is a challenge to continue to feel good when I think about the labor practices and environmental impact during each part of the process.

Ultimately, the report states that the fashion industry is broken due to its labor practices and resource utilization. Fashion relies on a model of unjust labor practices, overproduction, and steep discounts. Consumers are divorced from the idea of what something should actually cost, with negative externalities (inhumane labor practices, factory water runoff, etc.) factored into the price. In some ways, a $30 dress from Princess Polly is more expensive than a $300 dress from a small business on Etsy because of all the negative externalities built into that Princess Polly dress.

This situation is not sustainable, not from an environmental perspective, and not from a business perspective. How long can an industry stagger along, hemorrhaging talent and abusing the communities and ecosystems it relies upon to function? It is simply more profitable, in the current system, to overproduce and trash than to reduce production to reasonable levels.

Legislation on the supply chain, workers' rights, and negative consequences for overproduction is what will have the largest impact on the fashion industry. Fashion is a global industry. For broader, systemic change to occur, large and influential brands and retailers need to support legislation and binding agreements that hold themselves accountable for the human rights and environmental impacts.

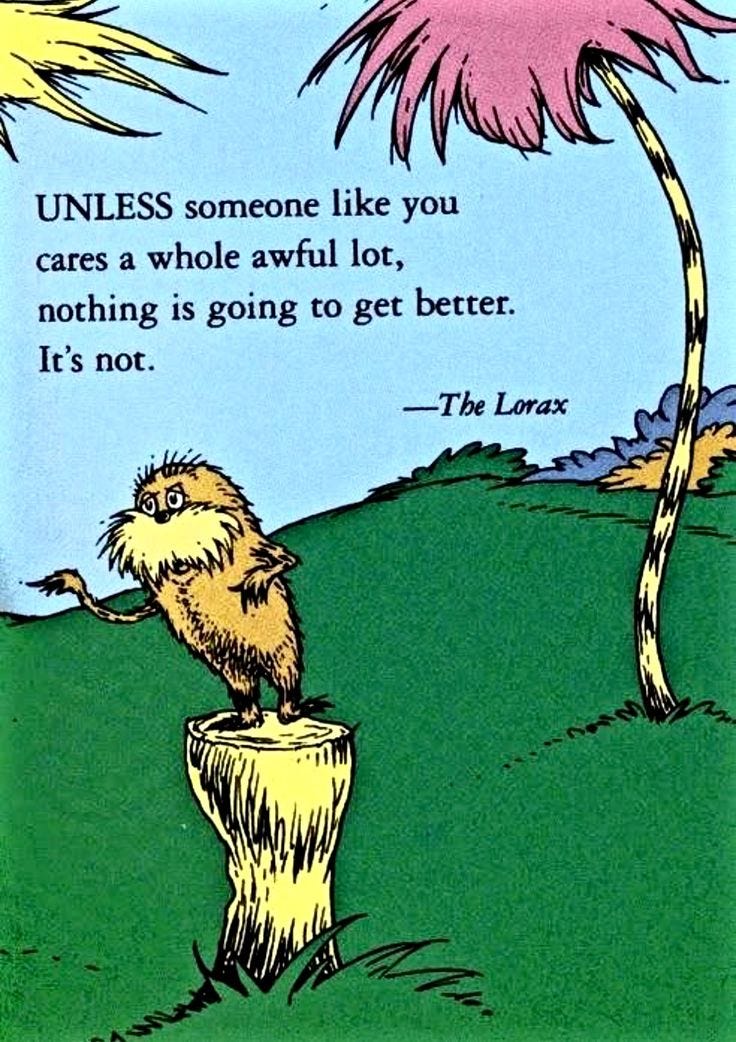

Until we all stop shopping and make our own clothes with cotton we’ve grown on our farms, fashion isn’t going to be sustainable. While that can be a depressing and defeatist message to hear, it can also be liberating, because anything we do will be an improvement. If we all take one small step, fashion will be more sustainable.

So, while I fully admit that stopping shopping altogether would be the best thing. Here are some ideas on a couple of things to get a bit closer:

Try to buy second-hand - whenever I need something new, my first stop is a second-hand website, TheRealReal, Vestiaire Collective, eBay, or Poshmark (although I tend to find Poshmark the most expensive). For skiing this winter, my whole outfit was sourced from eBay and Poshmark.

Fabric Composition - shoutout to my former colleague and fellow Substacker Eve, who first brought up to me the fabric composition and how many fabrics are made with plastic compositions. Apprx. 60% of the fabric produced is made of a plastic composition.

Before buying something new, befriend your tailor, cobbler and jewelry person to see if they can repair or remake something. Shoutout to my man Hector who is an absolute saint, on Greenwich Ave! Also check out this list for recommendations

Clothing Swaps - There are times when I have worn an item to death, but it still has some life left, and this is the perfect time to organize a clothing swap with friends. Everyone brings what they no longer want, and you get to go shopping in your friend’s closets! Nothing brings me more joy than my friend Elie wearing a dress I had grown tired of.

Borrow pieces from friends - if you have a wedding to go to, I most likely have a dress for you. I love my clothes and they deserve to go and see the world, so I’m always happy to have a friend borrow a dress, and I’ve borrowed friends’ dresses for weddings. (Although if you do this, best practice is to return it dry cleaned!)

Do further research than if it just says “sustainable” or “eco-friendly” - how does the brand define it? I always laugh to myself when I see eco-friendly or recycled materials from H&M because while it is a positive, it is a result of their overproduction.

Setting guardrails for myself - if I buy something, it has to fill a need or be a better version of something I already own. If not, it has to be an incredibly special item that I likely wouldn’t be able to find somewhere else and would be remiss to pass up. (i.e. my incredible coat I got at the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul)

Love all of you and mother Earth!

Love this. My journey has been similar to yours, and now I do the Rule of 5 (new) and the odd Vinted purchase (I try and sell enough to cover the cost of what I buy too). Also yes to looking at the labels! I don’t want to be wrapped in plastic, thank you 😂🤍